DitDC armies

THE ARMIES OF REI BOUBA

THE "SILENT CITY"

Modibbo

The first overlord of Rei Bouba was Modibbo

Adama, the first Emir of Yola (after whom the

region and people of Adamawa were apparently

named), who reigned from 1806 until 1848. Some

time early in his reign a man called Ardo Yajo

(whose family was originally from Mali) seized

power in Rei Bouba. It was his son Jidda who first

tried to break away from Yola and persuade the

Sultan of Sokoto to recognise him as an independent

Emir in his own right. The Sultan refused, and

Adama responded by attacking and occupying the

city of Rei. Jidda eventually drove him out and

pushed the Yola forces back into what is now

Nigeria, but although it was now effectively

autonomous, Rei Bouba continued to send a nominal

tribute in slaves to Yola until that Emirate was

conquered by the British in 1901. Jidda was

succeeded some time before 1872 by Buba Jirum,

who presided over a period of prosperity, and by the

end of the 19th century Rei Bouba had become one of

the three leading states of the Adamawa region.

The city of Rei Bouba can still be found on a

modern map under that name, south-east of Garoua

in the savannah country of northern Cameroon, not

far from the Chad border. The map, however, gives

no hint that this place was once a byword for

mystery, as remote and inaccessible as Timbuktu.

The people of Rei Bouba, who were known as the

Boubandjidda, were mainly of Fulani origin. The

Fulani were cattle herders, originally from Senegal,

who by the 18th century had spread across the

Western Sudan as far east as Darfur. By this time

they had adopted both the Muslim religion and the

cavalry tactics of the Hausa and other peoples with

whom they had mixed. At some time in the late 18th

century one group of Fulani advanced south of Lake

Chad, drove the inhabitants into the Mandara

Mountains, and established some sixty small

emirates in the upland region which was to become

known as Adamawa. The rulers of these mini states

were known by the title of “Lamidos”. They were

originally vassals of the Emir of Yola (just over the

border in present-day Nigeria), who was himself a

subject of the Emir of the great Hausa-Fulani

Emirate of Sokoto. In contrast to the situation further

north, where the Fulani devoted most of their

energies to fighting their fellow Muslims, those in

Adamawa regarded themselves as a sort of military

colony with the responsibility of guarding and

extending the frontiers of Islam, and they made little

effort to assimilate the pagan tribes, whom they

called “Kirdi”. Instead they subjected their

neighbours to continual slave raids, which according

to the elephant hunter “Karamoja” Bell were still

taking place after the First World War.

Bouba Gida

At the time of the German occupation of what

became their colony of Kamerun, the Lamido was a

notorious tyrant known as Bouba Gida, who had

allegedly murdered his own father and three of his

brothers in order to seize the throne. In fact there

were all sorts of stories about this mysterious

character; according to Bell he was the son of a

slave, who had started his own business as a slave

raider and had founded the present city of Rei Bouba

himself in a previously uninhabited spot. “The

whole organisation”, says Bell in a rather back-

handed tribute to the Lamido, “is an example of

what can be done by courage, energy, force of

character and extreme cunning allied to ferocity and

cruelty.” This remote area retained its independence

from European imperialism much longer than most

of Africa, but in 1899, as British, French and

German armies converged on the Lake Chad region,

extinguishing on the way the last of the independent

Fulani emirates, Rei Bouba finally fell under

German control.

By Chris Peers

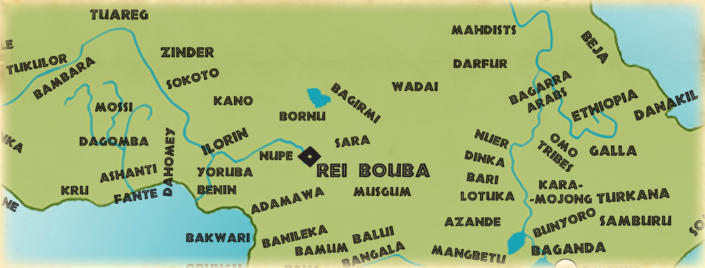

Map by the author showing positions of the tribes of Africa during this period, and showing the approximate

position of Rei Bouba: The "Silent City".

Lamido

However the new colonial authorities, impressed by

the good order maintained by the Lamido (and no

doubt by his “ferocity and cruelty”, which fitted in

perfectly with German ideas of how a colony should

be run), allowed him to retain his autonomy in

internal affairs, and perhaps for this reason the

conquest was carried out peacefully. When the First

World War broke out Bouba Gida provided men and

supplies for the German armies, but in early 1916,

when British and French forces were closing in on

the last German defenders of northern Kamerun, he

changed sides. After the war the French took over

this part of the country (which now became known

as Cameroun), and reaffirmed the autonomy of his

state as a reward for the Lamido’s timely assistance.

So it appears that it was principally due to the skill

and cunning of old Bouba Gida that Rei Bouba,

alone of the Adamawa emirates, survived into the

middle of the 20th century. Even after the Second

World War it remained what Bell calls “a remarkable

relic of the old slave-dealing days”, and one of the

very few places in colonial Africa “where a white

man’s actions are governed by a black man’s

wishes”.

Bouba Amadou

There were no European administrators in the

country, and even explorers and tourists were mostly

discouraged. Two well known British big-game

hunters, Major P. H. G. Powell-Cotton and Fred

Merfield, were allowed to visit Rei Bouba in the

early years of the 20th century in search of a rare

antelope, the giant eland (which they failed to find).

And shortly after the Second World War an Austrian

hunter, Ernst Zwilling, turned up to find the Sultan

still in power and his medieval army still on show.

Both Bouba Gida and his successor Bouba Amadou

obviously relished their position, and enjoyed

impressing their rare white visitors with their power

and authority. All three of our sources describe a

similar theatrical welcome. At the border they were

met by a sort of guard of honour, which conducted

them to the capital, and was joined along the way by

one contingent after another until they were being

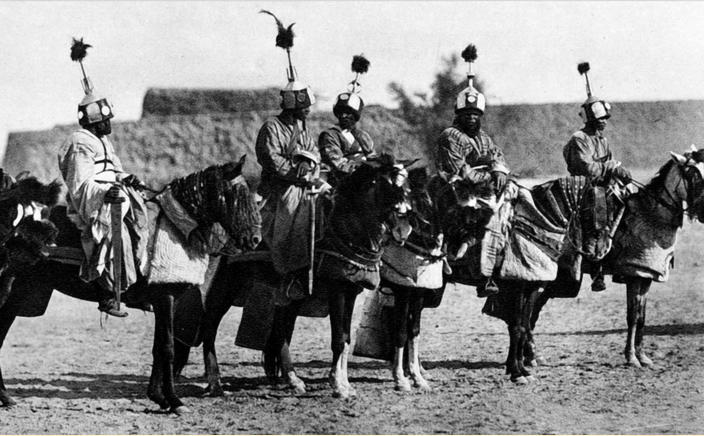

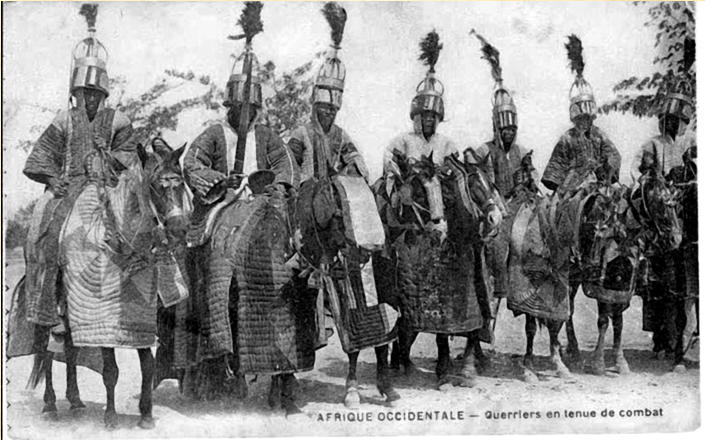

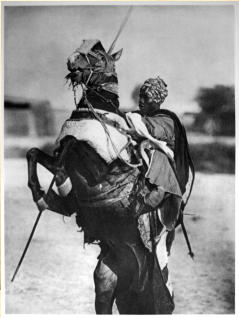

escorted by a small army. The most spectacular

element of this army was the heavy cavalry -

equipped in Hausa-Fulani style with mail or quilted

armour for both riders and horses - who saluted their

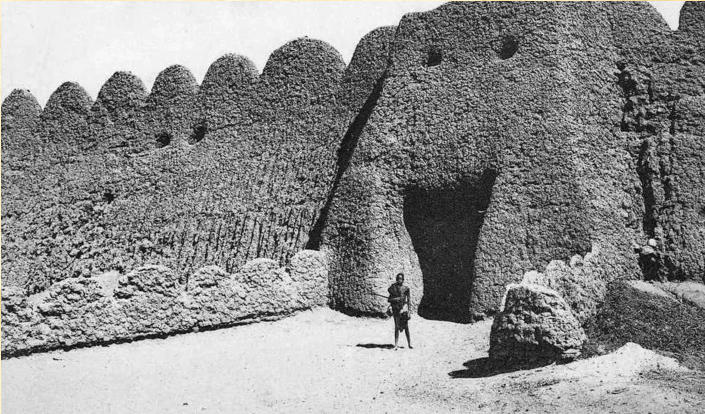

visitors with ferocious mock charges. The city of Rei

Bouba itself was surrounded by a wall of mud brick

20 feet high, with massive wooden gateways flanked

by guard houses set into the walls, which at these

points were 50 feet thick. The royal palace was

situated within an even stronger inner citadel,

enclosed by walls 40 or 50 feet in height. The

Lamido was certainly an odd character, who

occasionally allowed white visitors into his territory

and even paraded his army to impress them, but

scarcely deigned to speak to them himself, or to

allow his subjects to do so any more than was

absolutely necessary. Merfield’s experience was

particularly spooky, as he found the city completely

silent - apart from the muezzins’ calls to prayer - and

the streets deserted. No one was to be seen except

for the soldiers who provided the visitors’ guard of

honour and a handful of servants delegated to look

after them. Whether the “silent city”, as Merfield

calls it, was always like that, or whether the Sultan

had arranged it to impress his guests, is not clear, but

Bell confirms that singing, shouting and laughing

aloud were banned, as were music, costly dress and

ornamentation (except apparently among the

soldiers), and - inevitably - the drinking of alcohol.

Even inside the city the buildings were just ordinary

grass and wattle huts, as anything more ostentatious

was likewise forbidden. Another of the Lamido’s

eccentricities was his pet lion, which was led about

on a chain by one of his servants. As the lion was not

actually tame but was well known for his bad

temper, this was not exactly a popular job and staff

turnover was high. In fact Merfield was told that the

post was reserved for people who had upset the boss,

as an alternative to using the official executioner.

Costume

The “costume of the country”, says Zwilling, was a

short blue tunic, but men of substance were usually

dressed in one or more voluminous “tobes” of

various colours. A “tobe” was basically a huge

baggy shirt, usually but not always worn over

trousers. In one passage Zwilling mentions “lancers

in red tobes”, in another an officer in “blue and red

silk robes”, and elsewhere red fezzes and blue

“Phrygian caps”. The cavalry (and, Zwilling implies,

many of the infantry) wore iron helmets decorated

with ostrich plumes.

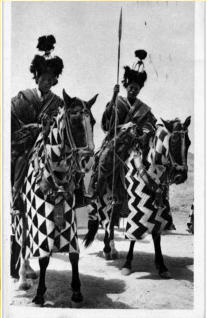

Merfield describes the armoured cavalry thus:

“Their horses were canopied with cloth of crude designs

and brilliant colours, covering the animals to their ears

and reaching down almost to their fetlocks. Some of

the riders wore mail, others were swathed in heavy robes,

with colourful, plumed headgear, and they all carried

spears with blades two feet long.”

Horse

Zwilling mentions horse caparisons in “a variety of

patterns - blue and white triangles or squares”. Both

he and Bell took black and white photographs

showing this horse armour patterned with checks (by

far the most common) or vertical stripes, in what

appear to be white and one or two other colours.

Zwilling also saw cavalrymen being followed by

pages on foot, who carried a reserve supply of

throwing spears. Merfield goes on to remark that

“they rode magnificently and had an uncanny

command of their horses”. The latter, Bell says, were

all stallions, which was general Hausa-Fulani

practice. According to Zwilling they were smallish

but well bred Arab-Berber steeds, whose daily ration

included half a calabash of beer (the animals being

presumably exempt from the religious ban on

alchohol). This contributed to their shining coats but

may not have done much for their fitness! It is

noteworthy that although these heavy cavalry were

typical of those found in the armies of the Fulani and

Hausa Emirates of the Western Sudan, none of our

sources mention the light cavalry which were

invariably in a majority further north. Adamawa was

home to some of the Shuwa Arabs who provided

much of the light cavalry for other Fulani armies,

and Rei Bouba was not far from the land of the

Musgum, who fought as light horsemen armed with

throwing knives. Therefore it seems likely that in the

days when Boubandjidda forces took the field in

earnest, rather than just to show off to visitors, they

would have been accompanied by at least some such

troops.

Infantry

The infantry were mainly spearmen and archers,

clad in tunics (presumably mostly blue), with

leopard skins draped over their shoulders. One of

Bell’s photographs shows a group of “commanders

of regiments” on foot, wearing what appear to be

long, elaborately decorated kilts. A rather crude

drawing from the same source depicts an archer in

what looks like a sleeveless shirt made of leopard

skin, and a plain knee-length kilt with trousers

underneath. He wears a fez on his head and a wide

sash or cummerbund round his waist, and has a

quiver slung on his back. His feet are apparently

bare. The spearmen had large shields made of

buffalo, rhinoceros or elephant hide which covered

most of their bodies, and the archers carried quivers

full of poisoned arrows on their backs. The guards

who escorted Merfield into the city carried an

assortment of “swords, axes, spears and

knobkerries”. Zwilling also mentions men armed

with “jagged” throwing knives. Though these

weapons were traditionally despised by the Fulani,

they were in practice carried even by Muslims, and

were especially popular among the non-Muslim

tribes of eastern Cameroun. In Zwilling’s time the

old Lamido’s successor, Bouba Amadou, had a

bodyguard of 50 men armed with guns of various

types and calibres (though the French authorities had

forbidden travellers to supply him with

ammunition), but this was probably a fairly recent

development. Most 19th century Fulani armies

obtained their firearms via the Sahara trade routes,

but these were a very long way from Rei Bouba.

Drums

Drums and trumpets accompanied all the military

exercises witnessed by the visitors, and no doubt had

done so in the field in the old days, as they did in

Fulani forces generally. Flags are not mentioned,

though they presumably existed and may have

resembled the ones carried by the armies of Sokoto;

these were white or blue, sometimes horizontally

striped, and occasionally carried inscriptions in

Arabic. One Bubandjidda nobleman was

accompanied by a servant with a red and white

striped parasol. It appears that by the early 20th

century the Lamido did not command his armies in

person on the slave raids which they still unofficially

conducted, but delegated the job to a subordinate,

who may himself have been a slave, or even a

eunuch. (Actually, according to Bell everyone in the

kingdom was technically a slave of the Lamido.)

The Wargames Army

82. REI BOUBA, 1890-1899.

The late 19th century army of Rei Bouba is one of the options covered by army list number 10 in my “Death

In The Dark Continent” rules, “The Hausa-Fulani Emirates”. The list below is, however, more specifically

focused on the “silent city” under the rule of Bouba Gida, and includes a couple of new features designed to

bring out its peculiar character.

•

Ag 1, Disciplined if the Chief is Bouba Gida, otherwise Organised.

•

Yan lifida: Protected Heavy Cavalry with close combat weapons only (10 points)

1–2

•

Shuwa Arab cavalry: Light Horse with spears (7 points)

0–1

•

Musgum cavalry: Light Horse with throwing knives (9 points)

0–1

•

Yam baka: Skirmishers with spears or bows (4 points), or throwing knives (6 points)

1–6

•

Guardsmen: Warriors (6 points) or Elite Skirmishers (8 points) with spears

0–1

Notes

A Chief representing Bouba Gida (1890 – 1899) may be Outstanding.

Any or all Heavy Cavalry may be upgraded to to Elite (+4 points).

Home terrain is Savannah.

Defences: Town walls, Tembes.

Stratagems: Drums.

Special Rule: Lion! We have no evidence that Bouba Gida’s pet lion actually accompanied the army into

battle, but we can speculate that it might have had an adverse effect on an enemy if it had done. So if the

Chief is Bouba Gida he can be accompanied by a base representing a lion being held on a chain by a slave,

which costs 20 points. The beast will not actually be let loose to fight, but the horses of enemy cavalry do not

know this, and the sound and smell of it may cause them to panic. So any opposing mounted unit which is

within 12 inches of the lion in the morale phase of a turn must take 2 morale tests for this cause. The lion

moves at normal Skirmisher rate and is shot at as if it was a single base Skirmisher unit. It cannot be moved

into close combat, but if an enemy contacts it it fights like an Elite Warrior base. It never needs to take morale

tests itself, though if it is killed friendly units need to test as usual for seeing a unit destroyed.

Sources:

W. D. M. Bell, “The Wanderings of an Elephant Hunter”.

London, 1923.

S. J. Hogben, “An Introduction to the History of the

Islamic states of Northern Nigeria”. Ibadan, 1967.

F. G. Merfield, “Gorillas Were My Neighbours”. London,

1957.

E. A. Zwilling, “Jungle Fever”. London, 1956.