The wonderful thing about our North Star 1672 range is that the figures will do for many different nations armies in the period 1665-1680. This is because it is a time just before uniforms, and the figures are all dressed in the fashions common amongst soldiers throughout Western Europe.

because it is a time just before uniforms, and the figures are all dressed in the fashions common amongst soldiers throughout Western Europe.

because it is a time just before uniforms, and the figures are all dressed in the fashions common amongst soldiers throughout Western Europe.

because it is a time just before uniforms, and the figures are all dressed in the fashions common amongst soldiers throughout Western Europe.

This of course includes Britain. The years covered by our range is called the Restoration Period in

The years covered by our range is called the Restoration Period in Britain as it was the time the monarchy, represented by Charles II,

Britain as it was the time the monarchy, represented by Charles II,  was restored after the English Civil War.

was restored after the English Civil War.  It was also the genesis of the British Army. Britain, tired of soldiers

It was also the genesis of the British Army. Britain, tired of soldiers and war, had disbanded much of it’s forces after the Civil War and

and war, had disbanded much of it’s forces after the Civil War and Oliver Cromwell’s reign. With the return of Charles II to England in

Oliver Cromwell’s reign. With the return of Charles II to England in 1660, the units still under arms swore allegiance to the King and

1660, the units still under arms swore allegiance to the King and became the senior units of the British Army.

Some of the infantry regiments:

became the senior units of the British Army.

Some of the infantry regiments: Coldstream Guards

Grenadier Guards

Scots Guards

1st Regiment (Royal Scots)

2nd Regiment (The Queen’s)

3rd Regiment (The Buffs)

st

Coldstream Guards

Grenadier Guards

Scots Guards

1st Regiment (Royal Scots)

2nd Regiment (The Queen’s)

3rd Regiment (The Buffs)

st

The years covered by our range is called the Restoration Period in

The years covered by our range is called the Restoration Period in Britain as it was the time the monarchy, represented by Charles II,

Britain as it was the time the monarchy, represented by Charles II,  was restored after the English Civil War.

was restored after the English Civil War.  It was also the genesis of the British Army. Britain, tired of soldiers

It was also the genesis of the British Army. Britain, tired of soldiers and war, had disbanded much of it’s forces after the Civil War and

and war, had disbanded much of it’s forces after the Civil War and Oliver Cromwell’s reign. With the return of Charles II to England in

Oliver Cromwell’s reign. With the return of Charles II to England in 1660, the units still under arms swore allegiance to the King and

1660, the units still under arms swore allegiance to the King and became the senior units of the British Army.

Some of the infantry regiments:

became the senior units of the British Army.

Some of the infantry regiments: Coldstream Guards

Grenadier Guards

Scots Guards

1st Regiment (Royal Scots)

2nd Regiment (The Queen’s)

3rd Regiment (The Buffs)

st

Coldstream Guards

Grenadier Guards

Scots Guards

1st Regiment (Royal Scots)

2nd Regiment (The Queen’s)

3rd Regiment (The Buffs)

st

Colour.

emerged alive.” In Livingstone’s day it seems that one way of getting rid of nosy visitors to the region was to provide them

getting rid of nosy visitors to the region was to provide them with a guide with secret instructions to lead them into the

with a guide with secret instructions to lead them into the country of the Ila, who could then be relied on to do the dirty

country of the Ila, who could then be relied on to do the dirty work. Coillard, writing in 1888, listed several explorers and

work. Coillard, writing in 1888, listed several explorers and traders who had disappeared and were believed to have been

traders who had disappeared and were believed to have been killed by the Ila. However in the 1880s a couple of their

killed by the Ila. However in the 1880s a couple of their intended victims managed to get away to tell the tale. The first

intended victims managed to get away to tell the tale. The first of these was the Bohemian explorer Dr. Emil Holub, who

of these was the Bohemian explorer Dr. Emil Holub, who arrived in the country in 1886 with his wife and a colleague

arrived in the country in 1886 with his wife and a colleague named Oswald Sollner. The couple were saved from an Ila

named Oswald Sollner. The couple were saved from an Ila war party by an amazing display of shooting by Mrs. Holub,

war party by an amazing display of shooting by Mrs. Holub, but Sollner was speared to death and the survivors fled from

but Sollner was speared to death and the survivors fled from the country. Then in 1888 the famous elephant hunter F. C.

the country. Then in 1888 the famous elephant hunter F. C. Selous arrived in Ila territory - apparently by mistake, as he

Selous arrived in Ila territory - apparently by mistake, as he knew all about the Holubs’ experience and had sensibly

knew all about the Holubs’ experience and had sensibly intended to avoid the area. One evening, while he was

intended to avoid the area. One evening, while he was encamped outside the village of a chief named Minenga, he

encamped outside the village of a chief named Minenga, he was on the receiving end of a shower of spears, the prelude to

was on the receiving end of a shower of spears, the prelude to the inevitable rush. He managed to escape into a patch of tall

the inevitable rush. He managed to escape into a patch of tall grass but had to leave his rifle behind. Despite this record of

grass but had to leave his rifle behind. Despite this record of violence the Ila received a visit soon afterwards by some

violence the Ila received a visit soon afterwards by some brave Methodist missionaries, and proved surprisingly

brave Methodist missionaries, and proved surprisingly welcoming. By 1900 they had all meekly accepted British

welcoming. By 1900 they had all meekly accepted British rule. It is likely that after the attentions of their predatory

rule. It is likely that after the attentions of their predatory neighbours they were well aware of the benefits of the “Pax

neighbours they were well aware of the benefits of the “Pax Britannica”.

Britannica”.  Ila Warfare

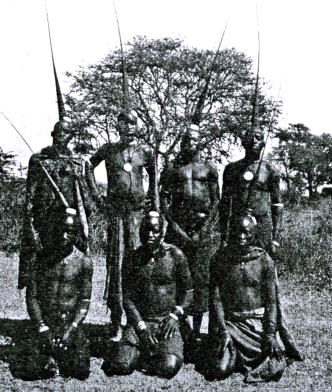

Ila warriors were particularly expert with their favourite

Ila Warfare

Ila warriors were particularly expert with their favourite weapon, the throwing spear. They did not use shields, but

weapon, the throwing spear. They did not use shields, but instead would carry an elephant’s tail, or a bunch of feathers

instead would carry an elephant’s tail, or a bunch of feathers on the end of stick, which could be twirled to distract an

on the end of stick, which could be twirled to distract an

getting rid of nosy visitors to the region was to provide them

getting rid of nosy visitors to the region was to provide them with a guide with secret instructions to lead them into the

with a guide with secret instructions to lead them into the country of the Ila, who could then be relied on to do the dirty

country of the Ila, who could then be relied on to do the dirty work. Coillard, writing in 1888, listed several explorers and

work. Coillard, writing in 1888, listed several explorers and traders who had disappeared and were believed to have been

traders who had disappeared and were believed to have been killed by the Ila. However in the 1880s a couple of their

killed by the Ila. However in the 1880s a couple of their intended victims managed to get away to tell the tale. The first

intended victims managed to get away to tell the tale. The first of these was the Bohemian explorer Dr. Emil Holub, who

of these was the Bohemian explorer Dr. Emil Holub, who arrived in the country in 1886 with his wife and a colleague

arrived in the country in 1886 with his wife and a colleague named Oswald Sollner. The couple were saved from an Ila

named Oswald Sollner. The couple were saved from an Ila war party by an amazing display of shooting by Mrs. Holub,

war party by an amazing display of shooting by Mrs. Holub, but Sollner was speared to death and the survivors fled from

but Sollner was speared to death and the survivors fled from the country. Then in 1888 the famous elephant hunter F. C.

the country. Then in 1888 the famous elephant hunter F. C. Selous arrived in Ila territory - apparently by mistake, as he

Selous arrived in Ila territory - apparently by mistake, as he knew all about the Holubs’ experience and had sensibly

knew all about the Holubs’ experience and had sensibly intended to avoid the area. One evening, while he was

intended to avoid the area. One evening, while he was encamped outside the village of a chief named Minenga, he

encamped outside the village of a chief named Minenga, he was on the receiving end of a shower of spears, the prelude to

was on the receiving end of a shower of spears, the prelude to the inevitable rush. He managed to escape into a patch of tall

the inevitable rush. He managed to escape into a patch of tall grass but had to leave his rifle behind. Despite this record of

grass but had to leave his rifle behind. Despite this record of violence the Ila received a visit soon afterwards by some

violence the Ila received a visit soon afterwards by some brave Methodist missionaries, and proved surprisingly

brave Methodist missionaries, and proved surprisingly welcoming. By 1900 they had all meekly accepted British

welcoming. By 1900 they had all meekly accepted British rule. It is likely that after the attentions of their predatory

rule. It is likely that after the attentions of their predatory neighbours they were well aware of the benefits of the “Pax

neighbours they were well aware of the benefits of the “Pax Britannica”.

Britannica”.  Ila Warfare

Ila warriors were particularly expert with their favourite

Ila Warfare

Ila warriors were particularly expert with their favourite weapon, the throwing spear. They did not use shields, but

weapon, the throwing spear. They did not use shields, but instead would carry an elephant’s tail, or a bunch of feathers

instead would carry an elephant’s tail, or a bunch of feathers on the end of stick, which could be twirled to distract an

on the end of stick, which could be twirled to distract an

enemy’s aim. (Some ideas for figure conversions there. They were keen head hunters, so it would also be appropriate to add a

few severed heads to the tips of their spears.) Men who wished

were keen head hunters, so it would also be appropriate to add a

few severed heads to the tips of their spears.) Men who wished to show their contempt for an enemy spearman whose throw

to show their contempt for an enemy spearman whose throw had missed would ostentatiously sweep the ground in front of

had missed would ostentatiously sweep the ground in front of them, a display of coolness which was much admired by their

them, a display of coolness which was much admired by their comrades. Otherwise they relied entirely on speed and mobility

comrades. Otherwise they relied entirely on speed and mobility for protection against missiles. In the colonial era the Ila

for protection against missiles. In the colonial era the Ila continued to perform dances which resembled mock battles, in

continued to perform dances which resembled mock battles, in which the warriors could practice their spear throwing and

which the warriors could practice their spear throwing and dodging skills. Even the young boys were said to be able to

dodging skills. Even the young boys were said to be able to throw their spears accurately up to 50 yards, while the longest

throw their spears accurately up to 50 yards, while the longest throw recorded was an incredible 75 yards.

throw recorded was an incredible 75 yards.  They produced a variety of spear types, designed for different

They produced a variety of spear types, designed for different tasks in hunting and warfare. These included the spike-headed

tasks in hunting and warfare. These included the spike-headed “mumba”, which was the first to be thrown in an engagement

“mumba”, which was the first to be thrown in an engagement and was presumably optimised for long range; the short, broad-

and was presumably optimised for long range; the short, broad- headed “impengula”, which resembled a Zulu “iklwa” and was

headed “impengula”, which resembled a Zulu “iklwa” and was similarly used for thrusting at close quarters; and the viciously

similarly used for thrusting at close quarters; and the viciously barbed “lukona”, a specialised war spear. In internal Ila battles

barbed “lukona”, a specialised war spear. In internal Ila battles the warriors relied on retrieving spears thrown by their

the warriors relied on retrieving spears thrown by their opponents, and this sort of exchange could continue for many

opponents, and this sort of exchange could continue for many hours, but against enemies like the Matabele and Barotse, who

hours, but against enemies like the Matabele and Barotse, who tended to discharge a few volleys and then close for hand-to-

tended to discharge a few volleys and then close for hand-to- hand fighting, the Ila were at a disadvantage because they

hand fighting, the Ila were at a disadvantage because they quickly ran out of missiles. The recollections of veterans of the

quickly ran out of missiles. The recollections of veterans of the Barotse wars suggest that the Ila were not well prepared for

Barotse wars suggest that the Ila were not well prepared for hand-to-hand combat, and were all too often knocked on the

hand-to-hand combat, and were all too often knocked on the head with knobkerries while looking around for something to

head with knobkerries while looking around for something to throw. But as mentioned above they did have spears which were

obviously designed for stabbing at close quarters, so they can

throw. But as mentioned above they did have spears which were

obviously designed for stabbing at close quarters, so they can hardly have been completely helpless.

hardly have been completely helpless.

were keen head hunters, so it would also be appropriate to add a

few severed heads to the tips of their spears.) Men who wished

were keen head hunters, so it would also be appropriate to add a

few severed heads to the tips of their spears.) Men who wished to show their contempt for an enemy spearman whose throw

to show their contempt for an enemy spearman whose throw had missed would ostentatiously sweep the ground in front of

had missed would ostentatiously sweep the ground in front of them, a display of coolness which was much admired by their

them, a display of coolness which was much admired by their comrades. Otherwise they relied entirely on speed and mobility

comrades. Otherwise they relied entirely on speed and mobility for protection against missiles. In the colonial era the Ila

for protection against missiles. In the colonial era the Ila continued to perform dances which resembled mock battles, in

continued to perform dances which resembled mock battles, in which the warriors could practice their spear throwing and

which the warriors could practice their spear throwing and dodging skills. Even the young boys were said to be able to

dodging skills. Even the young boys were said to be able to throw their spears accurately up to 50 yards, while the longest

throw their spears accurately up to 50 yards, while the longest throw recorded was an incredible 75 yards.

throw recorded was an incredible 75 yards.  They produced a variety of spear types, designed for different

They produced a variety of spear types, designed for different tasks in hunting and warfare. These included the spike-headed

tasks in hunting and warfare. These included the spike-headed “mumba”, which was the first to be thrown in an engagement

“mumba”, which was the first to be thrown in an engagement and was presumably optimised for long range; the short, broad-

and was presumably optimised for long range; the short, broad- headed “impengula”, which resembled a Zulu “iklwa” and was

headed “impengula”, which resembled a Zulu “iklwa” and was similarly used for thrusting at close quarters; and the viciously

similarly used for thrusting at close quarters; and the viciously barbed “lukona”, a specialised war spear. In internal Ila battles

barbed “lukona”, a specialised war spear. In internal Ila battles the warriors relied on retrieving spears thrown by their

the warriors relied on retrieving spears thrown by their opponents, and this sort of exchange could continue for many

opponents, and this sort of exchange could continue for many hours, but against enemies like the Matabele and Barotse, who

hours, but against enemies like the Matabele and Barotse, who tended to discharge a few volleys and then close for hand-to-

tended to discharge a few volleys and then close for hand-to- hand fighting, the Ila were at a disadvantage because they

hand fighting, the Ila were at a disadvantage because they quickly ran out of missiles. The recollections of veterans of the

quickly ran out of missiles. The recollections of veterans of the Barotse wars suggest that the Ila were not well prepared for

Barotse wars suggest that the Ila were not well prepared for hand-to-hand combat, and were all too often knocked on the

hand-to-hand combat, and were all too often knocked on the head with knobkerries while looking around for something to

head with knobkerries while looking around for something to throw. But as mentioned above they did have spears which were

obviously designed for stabbing at close quarters, so they can

throw. But as mentioned above they did have spears which were

obviously designed for stabbing at close quarters, so they can hardly have been completely helpless.

hardly have been completely helpless.

Below. Young Ila warriors with freshly done hair cone or

“isusu”.

Above. Chief Shimunungu and two of his men.