The wonderful thing about our North Star 1672 range is that the figures will do for many different nations armies in the period 1665-1680. This is because it is a time just before uniforms, and the figures are all dressed in the fashions common amongst soldiers throughout Western Europe.

because it is a time just before uniforms, and the figures are all dressed in the fashions common amongst soldiers throughout Western Europe.

because it is a time just before uniforms, and the figures are all dressed in the fashions common amongst soldiers throughout Western Europe.

because it is a time just before uniforms, and the figures are all dressed in the fashions common amongst soldiers throughout Western Europe.

This of course includes Britain. The years covered by our range is called the Restoration Period in

The years covered by our range is called the Restoration Period in Britain as it was the time the monarchy, represented by Charles II,

Britain as it was the time the monarchy, represented by Charles II,  was restored after the English Civil War.

was restored after the English Civil War.  It was also the genesis of the British Army. Britain, tired of soldiers

It was also the genesis of the British Army. Britain, tired of soldiers and war, had disbanded much of it’s forces after the Civil War and

and war, had disbanded much of it’s forces after the Civil War and Oliver Cromwell’s reign. With the return of Charles II to England in

Oliver Cromwell’s reign. With the return of Charles II to England in 1660, the units still under arms swore allegiance to the King and

1660, the units still under arms swore allegiance to the King and became the senior units of the British Army.

Some of the infantry regiments:

became the senior units of the British Army.

Some of the infantry regiments: Coldstream Guards

Grenadier Guards

Scots Guards

1st Regiment (Royal Scots)

2nd Regiment (The Queen’s)

3rd Regiment (The Buffs)

st

Coldstream Guards

Grenadier Guards

Scots Guards

1st Regiment (Royal Scots)

2nd Regiment (The Queen’s)

3rd Regiment (The Buffs)

st

The years covered by our range is called the Restoration Period in

The years covered by our range is called the Restoration Period in Britain as it was the time the monarchy, represented by Charles II,

Britain as it was the time the monarchy, represented by Charles II,  was restored after the English Civil War.

was restored after the English Civil War.  It was also the genesis of the British Army. Britain, tired of soldiers

It was also the genesis of the British Army. Britain, tired of soldiers and war, had disbanded much of it’s forces after the Civil War and

and war, had disbanded much of it’s forces after the Civil War and Oliver Cromwell’s reign. With the return of Charles II to England in

Oliver Cromwell’s reign. With the return of Charles II to England in 1660, the units still under arms swore allegiance to the King and

1660, the units still under arms swore allegiance to the King and became the senior units of the British Army.

Some of the infantry regiments:

became the senior units of the British Army.

Some of the infantry regiments: Coldstream Guards

Grenadier Guards

Scots Guards

1st Regiment (Royal Scots)

2nd Regiment (The Queen’s)

3rd Regiment (The Buffs)

st

Coldstream Guards

Grenadier Guards

Scots Guards

1st Regiment (Royal Scots)

2nd Regiment (The Queen’s)

3rd Regiment (The Buffs)

st

Colour.

Guns

They did not despise guns, though, and the new weapons became increasingly common in the second half of the

became increasingly common in the second half of the nineteenth century. At first they were the usual African trade

nineteenth century. At first they were the usual African trade muskets, cheap muzzle-loaders and worn out elephant guns,

muskets, cheap muzzle-loaders and worn out elephant guns, but by the 1890s modern rifles were being imported in large

but by the 1890s modern rifles were being imported in large quantities. In 1889 the infamous "Rudd Concession", one of

quantities. In 1889 the infamous "Rudd Concession", one of several attempts by the white men to con Lobengula out of his

kingdom, promised him 1,000 Martini Henrys and 100,000

several attempts by the white men to con Lobengula out of his

kingdom, promised him 1,000 Martini Henrys and 100,000 rounds of ammunition, and most of this seems to have been

rounds of ammunition, and most of this seems to have been delivered. In fact in the war of 1893 the Matabele possessed

delivered. In fact in the war of 1893 the Matabele possessed more breechloaders than their white opponents. But firearms

more breechloaders than their white opponents. But firearms never displaced spears as the main fighting arm, and were

never displaced spears as the main fighting arm, and were seldom employed very effectively. F. C. Selous visited

seldom employed very effectively. F. C. Selous visited Lobengula not long after the battle which brought him to

Lobengula not long after the battle which brought him to power in 1870, and was told by a hunter named Philips, who

power in 1870, and was told by a hunter named Philips, who had treated the wounded after the battle, that although both

had treated the wounded after the battle, that although both sides possessed large numbers of muskets nearly all the

sides possessed large numbers of muskets nearly all the wounds were caused by spears, mostly at very close quarters:

wounds were caused by spears, mostly at very close quarters: "In many instances he found two men lying dead together,

"In many instances he found two men lying dead together, each with the other's assegai through his heart." In 1893 the

each with the other's assegai through his heart." In 1893 the war correspondent C. L. Norris- Newman concluded that the

war correspondent C. L. Norris- Newman concluded that the Matabele were still poor shots, but were "much more

Matabele were still poor shots, but were "much more dangerous" with the assegai.

Decline

It is often argued that the Matabele had declined in various

dangerous" with the assegai.

Decline

It is often argued that the Matabele had declined in various ways from the high standards which existed in Zululand. Their

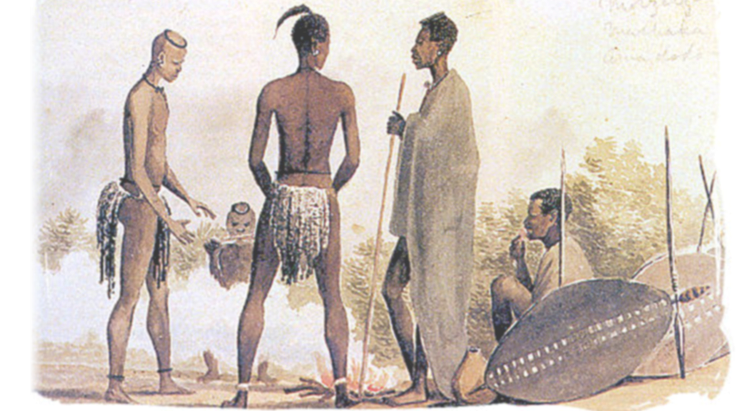

ways from the high standards which existed in Zululand. Their dress uniforms were less elaborate, their shields less carefully

dress uniforms were less elaborate, their shields less carefully made, and their stabbing assegais had smaller blades (in fact

made, and their stabbing assegais had smaller blades (in fact these were often old Zulu ones which had been repeatedly

these were often old Zulu ones which had been repeatedly resharpened). Norris-Newman, who had been in the Zulu War

resharpened). Norris-Newman, who had been in the Zulu War of 1879 as well as the Matabele campaign of 1893, thought

of 1879 as well as the Matabele campaign of 1893, thought

became increasingly common in the second half of the

became increasingly common in the second half of the nineteenth century. At first they were the usual African trade

nineteenth century. At first they were the usual African trade muskets, cheap muzzle-loaders and worn out elephant guns,

muskets, cheap muzzle-loaders and worn out elephant guns, but by the 1890s modern rifles were being imported in large

but by the 1890s modern rifles were being imported in large quantities. In 1889 the infamous "Rudd Concession", one of

quantities. In 1889 the infamous "Rudd Concession", one of several attempts by the white men to con Lobengula out of his

kingdom, promised him 1,000 Martini Henrys and 100,000

several attempts by the white men to con Lobengula out of his

kingdom, promised him 1,000 Martini Henrys and 100,000 rounds of ammunition, and most of this seems to have been

rounds of ammunition, and most of this seems to have been delivered. In fact in the war of 1893 the Matabele possessed

delivered. In fact in the war of 1893 the Matabele possessed more breechloaders than their white opponents. But firearms

more breechloaders than their white opponents. But firearms never displaced spears as the main fighting arm, and were

never displaced spears as the main fighting arm, and were seldom employed very effectively. F. C. Selous visited

seldom employed very effectively. F. C. Selous visited Lobengula not long after the battle which brought him to

Lobengula not long after the battle which brought him to power in 1870, and was told by a hunter named Philips, who

power in 1870, and was told by a hunter named Philips, who had treated the wounded after the battle, that although both

had treated the wounded after the battle, that although both sides possessed large numbers of muskets nearly all the

sides possessed large numbers of muskets nearly all the wounds were caused by spears, mostly at very close quarters:

wounds were caused by spears, mostly at very close quarters: "In many instances he found two men lying dead together,

"In many instances he found two men lying dead together, each with the other's assegai through his heart." In 1893 the

each with the other's assegai through his heart." In 1893 the war correspondent C. L. Norris- Newman concluded that the

war correspondent C. L. Norris- Newman concluded that the Matabele were still poor shots, but were "much more

Matabele were still poor shots, but were "much more dangerous" with the assegai.

Decline

It is often argued that the Matabele had declined in various

dangerous" with the assegai.

Decline

It is often argued that the Matabele had declined in various ways from the high standards which existed in Zululand. Their

ways from the high standards which existed in Zululand. Their dress uniforms were less elaborate, their shields less carefully

dress uniforms were less elaborate, their shields less carefully made, and their stabbing assegais had smaller blades (in fact

made, and their stabbing assegais had smaller blades (in fact these were often old Zulu ones which had been repeatedly

these were often old Zulu ones which had been repeatedly resharpened). Norris-Newman, who had been in the Zulu War

resharpened). Norris-Newman, who had been in the Zulu War of 1879 as well as the Matabele campaign of 1893, thought

of 1879 as well as the Matabele campaign of 1893, thought

that overall they were "not as brave" as the Zulus. Nevertheless

their neighbours continued to regard them with a mixture of awe and terror, and under Lobengula the warriors' training

awe and terror, and under Lobengula the warriors' training regime could still be extremely tough. In the 1870s the explorer

regime could still be extremely tough. In the 1870s the explorer Emil Holub collected accounts of the training regime of the

Emil Holub collected accounts of the training regime of the Matabele armies, and claimed that although high class "Zansi"

Matabele armies, and claimed that although high class "Zansi" boys were raised in rather leisurely fashion in their fathers'

boys were raised in rather leisurely fashion in their fathers' kraals, perhaps relying on their natural sense of social

kraals, perhaps relying on their natural sense of social superiority to motivate them in battle, the training of prisoners

superiority to motivate them in battle, the training of prisoners of war and other non-Matabele recruits was far more rigorous.

of war and other non-Matabele recruits was far more rigorous. On one occasion only one hundred and seventeen out of a

On one occasion only one hundred and seventeen out of a hundred and sixty recruits survived the training period. This is

hundred and sixty recruits survived the training period. This is not surprising if some of the more lurid stories are true. Holub

not surprising if some of the more lurid stories are true. Holub says that, apart from fatigues, route marches and mock fights

says that, apart from fatigues, route marches and mock fights with clubs, one task involved killing a wild hyaena with a stick.

with clubs, one task involved killing a wild hyaena with a stick. A former Shona captive quoted by Summers and Pagden adds

A former Shona captive quoted by Summers and Pagden adds that groups of young warriors would be sent to kill buffalos

that groups of young warriors would be sent to kill buffalos with clubs, and even to tackle lions bare-handed. Selous

with clubs, and even to tackle lions bare-handed. Selous remarked that the man-eating lions which plagued other parts of

remarked that the man-eating lions which plagued other parts of the continent were almost unknown in Matabeleland, where the

the continent were almost unknown in Matabeleland, where the lions were scared of the people rather the other way around! In

lions were scared of the people rather the other way around! In this context the story told by the elephant hunter William

this context the story told by the elephant hunter William Finaughty, of Mzilikazi ordering one of his regiments to haul a

Finaughty, of Mzilikazi ordering one of his regiments to haul a man-eating crocodile out of a river and bring it to him alive, can

man-eating crocodile out of a river and bring it to him alive, can be seen not as the whim of a capricious tyrant, but as part of a

be seen not as the whim of a capricious tyrant, but as part of a consistent policy of accustoming young warriors to hardship

consistent policy of accustoming young warriors to hardship and bloodshed. The deliberate brutalisation of young captives

and bloodshed. The deliberate brutalisation of young captives and conscripts has chilling parallels to the use of child soldiers

and conscripts has chilling parallels to the use of child soldiers in Africa today. The Legend.

Fall of the kingdom

After the fall of the Matabele kingdom all sorts of romantic

in Africa today. The Legend.

Fall of the kingdom

After the fall of the Matabele kingdom all sorts of romantic legends circulated about the whereabouts of Lobengula's

legends circulated about the whereabouts of Lobengula's supposed hoard of gold and diamonds. According to the best

supposed hoard of gold and diamonds. According to the best

awe and terror, and under Lobengula the warriors' training

awe and terror, and under Lobengula the warriors' training regime could still be extremely tough. In the 1870s the explorer

regime could still be extremely tough. In the 1870s the explorer Emil Holub collected accounts of the training regime of the

Emil Holub collected accounts of the training regime of the Matabele armies, and claimed that although high class "Zansi"

Matabele armies, and claimed that although high class "Zansi" boys were raised in rather leisurely fashion in their fathers'

boys were raised in rather leisurely fashion in their fathers' kraals, perhaps relying on their natural sense of social

kraals, perhaps relying on their natural sense of social superiority to motivate them in battle, the training of prisoners

superiority to motivate them in battle, the training of prisoners of war and other non-Matabele recruits was far more rigorous.

of war and other non-Matabele recruits was far more rigorous. On one occasion only one hundred and seventeen out of a

On one occasion only one hundred and seventeen out of a hundred and sixty recruits survived the training period. This is

hundred and sixty recruits survived the training period. This is not surprising if some of the more lurid stories are true. Holub

not surprising if some of the more lurid stories are true. Holub says that, apart from fatigues, route marches and mock fights

says that, apart from fatigues, route marches and mock fights with clubs, one task involved killing a wild hyaena with a stick.

with clubs, one task involved killing a wild hyaena with a stick. A former Shona captive quoted by Summers and Pagden adds

A former Shona captive quoted by Summers and Pagden adds that groups of young warriors would be sent to kill buffalos

that groups of young warriors would be sent to kill buffalos with clubs, and even to tackle lions bare-handed. Selous

with clubs, and even to tackle lions bare-handed. Selous remarked that the man-eating lions which plagued other parts of

remarked that the man-eating lions which plagued other parts of the continent were almost unknown in Matabeleland, where the

the continent were almost unknown in Matabeleland, where the lions were scared of the people rather the other way around! In

lions were scared of the people rather the other way around! In this context the story told by the elephant hunter William

this context the story told by the elephant hunter William Finaughty, of Mzilikazi ordering one of his regiments to haul a

Finaughty, of Mzilikazi ordering one of his regiments to haul a man-eating crocodile out of a river and bring it to him alive, can

man-eating crocodile out of a river and bring it to him alive, can be seen not as the whim of a capricious tyrant, but as part of a

be seen not as the whim of a capricious tyrant, but as part of a consistent policy of accustoming young warriors to hardship

consistent policy of accustoming young warriors to hardship and bloodshed. The deliberate brutalisation of young captives

and bloodshed. The deliberate brutalisation of young captives and conscripts has chilling parallels to the use of child soldiers

and conscripts has chilling parallels to the use of child soldiers in Africa today. The Legend.

Fall of the kingdom

After the fall of the Matabele kingdom all sorts of romantic

in Africa today. The Legend.

Fall of the kingdom

After the fall of the Matabele kingdom all sorts of romantic legends circulated about the whereabouts of Lobengula's

legends circulated about the whereabouts of Lobengula's supposed hoard of gold and diamonds. According to the best

supposed hoard of gold and diamonds. According to the best