The wonderful thing about our North Star 1672 range is that the figures will do for many different nations armies in the period 1665-1680. This is because it is a time just before uniforms, and the figures are all dressed in the fashions common amongst soldiers throughout Western Europe.

because it is a time just before uniforms, and the figures are all dressed in the fashions common amongst soldiers throughout Western Europe.

because it is a time just before uniforms, and the figures are all dressed in the fashions common amongst soldiers throughout Western Europe.

because it is a time just before uniforms, and the figures are all dressed in the fashions common amongst soldiers throughout Western Europe.

This of course includes Britain. The years covered by our range is called the Restoration Period in

The years covered by our range is called the Restoration Period in Britain as it was the time the monarchy, represented by Charles II,

Britain as it was the time the monarchy, represented by Charles II,  was restored after the English Civil War.

was restored after the English Civil War.  It was also the genesis of the British Army. Britain, tired of soldiers

It was also the genesis of the British Army. Britain, tired of soldiers and war, had disbanded much of it’s forces after the Civil War and

and war, had disbanded much of it’s forces after the Civil War and Oliver Cromwell’s reign. With the return of Charles II to England in

Oliver Cromwell’s reign. With the return of Charles II to England in 1660, the units still under arms swore allegiance to the King and

1660, the units still under arms swore allegiance to the King and became the senior units of the British Army.

Some of the infantry regiments:

became the senior units of the British Army.

Some of the infantry regiments: Coldstream Guards

Grenadier Guards

Scots Guards

1st Regiment (Royal Scots)

2nd Regiment (The Queen’s)

3rd Regiment (The Buffs)

st

Coldstream Guards

Grenadier Guards

Scots Guards

1st Regiment (Royal Scots)

2nd Regiment (The Queen’s)

3rd Regiment (The Buffs)

st

The years covered by our range is called the Restoration Period in

The years covered by our range is called the Restoration Period in Britain as it was the time the monarchy, represented by Charles II,

Britain as it was the time the monarchy, represented by Charles II,  was restored after the English Civil War.

was restored after the English Civil War.  It was also the genesis of the British Army. Britain, tired of soldiers

It was also the genesis of the British Army. Britain, tired of soldiers and war, had disbanded much of it’s forces after the Civil War and

and war, had disbanded much of it’s forces after the Civil War and Oliver Cromwell’s reign. With the return of Charles II to England in

Oliver Cromwell’s reign. With the return of Charles II to England in 1660, the units still under arms swore allegiance to the King and

1660, the units still under arms swore allegiance to the King and became the senior units of the British Army.

Some of the infantry regiments:

became the senior units of the British Army.

Some of the infantry regiments: Coldstream Guards

Grenadier Guards

Scots Guards

1st Regiment (Royal Scots)

2nd Regiment (The Queen’s)

3rd Regiment (The Buffs)

st

Coldstream Guards

Grenadier Guards

Scots Guards

1st Regiment (Royal Scots)

2nd Regiment (The Queen’s)

3rd Regiment (The Buffs)

st

Colour.

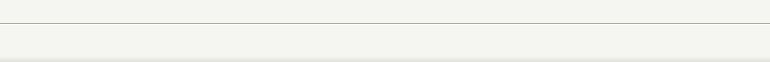

NSA1006 - Matabele Warriors in full Regalia

anything so fragile was still being worn on campaign in Lobengula's day.

Dress

As far as the rest of their dress was concerned, the Matabele

Lobengula's day.

Dress

As far as the rest of their dress was concerned, the Matabele superficially resembled Zulus but differed in a number of

superficially resembled Zulus but differed in a number of respects. At least some married men retained the head rings

respects. At least some married men retained the head rings (though they were smaller than the Zulu style and worn more

(though they were smaller than the Zulu style and worn more towards the front of the head) and otter skin headbands,

towards the front of the head) and otter skin headbands, though the latter became less common as time went on. Ox-

though the latter became less common as time went on. Ox- tail fringes on the arms and legs, however, remained popular.

tail fringes on the arms and legs, however, remained popular. The Samango or white-throated monkey whose skin was

The Samango or white-throated monkey whose skin was widely used in Zulu regalia was not found in Matabeleland,

widely used in Zulu regalia was not found in Matabeleland, though of course some warriors might still wear items which

though of course some warriors might still wear items which they or their fathers had brought from the south. Apparently

they or their fathers had brought from the south. Apparently the local vervet monkey was not much favoured, perhaps

the local vervet monkey was not much favoured, perhaps because it is a rather nondescript grey colour, and by

because it is a rather nondescript grey colour, and by Lobengula’s time kilts were more likely to be made from

Lobengula’s time kilts were more likely to be made from spotted cat skin or jackal tails (perhaps mixed together in the

spotted cat skin or jackal tails (perhaps mixed together in the same garment), or replaced in action with loincloths made of

same garment), or replaced in action with loincloths made of jackal or other fur. The rather scruffy looking “Matabele kilt”

jackal or other fur. The rather scruffy looking “Matabele kilt” seen in photos from the 1890s looks as if it is made up of any

seen in photos from the 1890s looks as if it is made up of any old strips of fur or skin, and should probably be painted in

old strips of fur or skin, and should probably be painted in various shades of light grey and brown. A cape made of

various shades of light grey and brown. A cape made of ostrich feathers or jackal fur might be worn around the

ostrich feathers or jackal fur might be worn around the shoulders, but this item was probably reserved mainly for

shoulders, but this item was probably reserved mainly for ceremonial occasions. Lobengula himself and his senior

ceremonial occasions. Lobengula himself and his senior "indunas" were sometimes depicted wearing leopard skin

"indunas" were sometimes depicted wearing leopard skin cloaks. Holi regiments would perhaps be more likely to take

cloaks. Holi regiments would perhaps be more likely to take the field in basic outfits consisting just of loincloths and

the field in basic outfits consisting just of loincloths and headdresses and I have a couple of such units made up of

headdresses and I have a couple of such units made up of Mark Copplestone's Watuta figures, just for variety. Based on

Mark Copplestone's Watuta figures, just for variety. Based on a similar survey of sketches made between the 1830s and the

a similar survey of sketches made between the 1830s and the 1870s, Summers and Pagden argue that when the Matabele

1870s, Summers and Pagden argue that when the Matabele began their migration to the north in the 1820s they were

began their migration to the north in the 1820s they were equipped like Shaka's "impis" with a single stabbing assegai

equipped like Shaka's "impis" with a single stabbing assegai (known to the Matabele as "isika"), and that the "isijula" or

(known to the Matabele as "isika"), and that the "isijula" or throwing spear was probably reinstated after Mzilikazi's death

throwing spear was probably reinstated after Mzilikazi's death in 1868 by his successor Lobengula. However Afrikaner

in 1868 by his successor Lobengula. However Afrikaner accounts of the Battle of Vegkop in 1836 describe spears

accounts of the Battle of Vegkop in 1836 describe spears being thrown into the laager, so missile weapons may actually

being thrown into the laager, so missile weapons may actually

Lobengula's day.

Dress

As far as the rest of their dress was concerned, the Matabele

Lobengula's day.

Dress

As far as the rest of their dress was concerned, the Matabele superficially resembled Zulus but differed in a number of

superficially resembled Zulus but differed in a number of respects. At least some married men retained the head rings

respects. At least some married men retained the head rings (though they were smaller than the Zulu style and worn more

(though they were smaller than the Zulu style and worn more towards the front of the head) and otter skin headbands,

towards the front of the head) and otter skin headbands, though the latter became less common as time went on. Ox-

though the latter became less common as time went on. Ox- tail fringes on the arms and legs, however, remained popular.

tail fringes on the arms and legs, however, remained popular. The Samango or white-throated monkey whose skin was

The Samango or white-throated monkey whose skin was widely used in Zulu regalia was not found in Matabeleland,

widely used in Zulu regalia was not found in Matabeleland, though of course some warriors might still wear items which

though of course some warriors might still wear items which they or their fathers had brought from the south. Apparently

they or their fathers had brought from the south. Apparently the local vervet monkey was not much favoured, perhaps

the local vervet monkey was not much favoured, perhaps because it is a rather nondescript grey colour, and by

because it is a rather nondescript grey colour, and by Lobengula’s time kilts were more likely to be made from

Lobengula’s time kilts were more likely to be made from spotted cat skin or jackal tails (perhaps mixed together in the

spotted cat skin or jackal tails (perhaps mixed together in the same garment), or replaced in action with loincloths made of

same garment), or replaced in action with loincloths made of jackal or other fur. The rather scruffy looking “Matabele kilt”

jackal or other fur. The rather scruffy looking “Matabele kilt” seen in photos from the 1890s looks as if it is made up of any

seen in photos from the 1890s looks as if it is made up of any old strips of fur or skin, and should probably be painted in

old strips of fur or skin, and should probably be painted in various shades of light grey and brown. A cape made of

various shades of light grey and brown. A cape made of ostrich feathers or jackal fur might be worn around the

ostrich feathers or jackal fur might be worn around the shoulders, but this item was probably reserved mainly for

shoulders, but this item was probably reserved mainly for ceremonial occasions. Lobengula himself and his senior

ceremonial occasions. Lobengula himself and his senior "indunas" were sometimes depicted wearing leopard skin

"indunas" were sometimes depicted wearing leopard skin cloaks. Holi regiments would perhaps be more likely to take

cloaks. Holi regiments would perhaps be more likely to take the field in basic outfits consisting just of loincloths and

the field in basic outfits consisting just of loincloths and headdresses and I have a couple of such units made up of

headdresses and I have a couple of such units made up of Mark Copplestone's Watuta figures, just for variety. Based on

Mark Copplestone's Watuta figures, just for variety. Based on a similar survey of sketches made between the 1830s and the

a similar survey of sketches made between the 1830s and the 1870s, Summers and Pagden argue that when the Matabele

1870s, Summers and Pagden argue that when the Matabele began their migration to the north in the 1820s they were

began their migration to the north in the 1820s they were equipped like Shaka's "impis" with a single stabbing assegai

equipped like Shaka's "impis" with a single stabbing assegai (known to the Matabele as "isika"), and that the "isijula" or

(known to the Matabele as "isika"), and that the "isijula" or throwing spear was probably reinstated after Mzilikazi's death

throwing spear was probably reinstated after Mzilikazi's death in 1868 by his successor Lobengula. However Afrikaner

in 1868 by his successor Lobengula. However Afrikaner accounts of the Battle of Vegkop in 1836 describe spears

accounts of the Battle of Vegkop in 1836 describe spears being thrown into the laager, so missile weapons may actually

being thrown into the laager, so missile weapons may actually

have reappeared at about the same time as Dingaan reintroduced them in the Zulu army. Alongside them, late 19th

reintroduced them in the Zulu army. Alongside them, late 19th century Matabele warriors carried an odd assortment of spears

century Matabele warriors carried an odd assortment of spears of various origins, including hunting and fishing weapons taken

from enemy tribes. Zulu-style knobkerries were also in use, and

of various origins, including hunting and fishing weapons taken

from enemy tribes. Zulu-style knobkerries were also in use, and a few illustrations from the 1890s show Sotho or Shona type

a few illustrations from the 1890s show Sotho or Shona type battle-axes. Matabele veterans denied that the latter were used

battle-axes. Matabele veterans denied that the latter were used in battle, but it is possible that some of the Holi may have

in battle, but it is possible that some of the Holi may have carried them unofficially. Interestingly, the “isika”, in contrast

carried them unofficially. Interestingly, the “isika”, in contrast to Zulu practice, were the property of the king rather than of the

to Zulu practice, were the property of the king rather than of the individual warriors. The aim of Matabele tactics, like those of

individual warriors. The aim of Matabele tactics, like those of the Zulus, was always ultimately to get to close quarters and

the Zulus, was always ultimately to get to close quarters and stab the enemy, and once this happened few opponents could

stab the enemy, and once this happened few opponents could resist for long. Moffat's informant quoted above refers to the

resist for long. Moffat's informant quoted above refers to the "clash of shields", and the "hissing and hollow groans" which

"clash of shields", and the "hissing and hollow groans" which served the Matabele for a war cry as they carved their way

served the Matabele for a war cry as they carved their way through the enemy ranks.

through the enemy ranks.

reintroduced them in the Zulu army. Alongside them, late 19th

reintroduced them in the Zulu army. Alongside them, late 19th century Matabele warriors carried an odd assortment of spears

century Matabele warriors carried an odd assortment of spears of various origins, including hunting and fishing weapons taken

from enemy tribes. Zulu-style knobkerries were also in use, and

of various origins, including hunting and fishing weapons taken

from enemy tribes. Zulu-style knobkerries were also in use, and a few illustrations from the 1890s show Sotho or Shona type

a few illustrations from the 1890s show Sotho or Shona type battle-axes. Matabele veterans denied that the latter were used

battle-axes. Matabele veterans denied that the latter were used in battle, but it is possible that some of the Holi may have

in battle, but it is possible that some of the Holi may have carried them unofficially. Interestingly, the “isika”, in contrast

carried them unofficially. Interestingly, the “isika”, in contrast to Zulu practice, were the property of the king rather than of the

to Zulu practice, were the property of the king rather than of the individual warriors. The aim of Matabele tactics, like those of

individual warriors. The aim of Matabele tactics, like those of the Zulus, was always ultimately to get to close quarters and

the Zulus, was always ultimately to get to close quarters and stab the enemy, and once this happened few opponents could

stab the enemy, and once this happened few opponents could resist for long. Moffat's informant quoted above refers to the

resist for long. Moffat's informant quoted above refers to the "clash of shields", and the "hissing and hollow groans" which

"clash of shields", and the "hissing and hollow groans" which served the Matabele for a war cry as they carved their way

served the Matabele for a war cry as they carved their way through the enemy ranks.

through the enemy ranks.